For ease of reference, figures in brackets refer to the reference numbers appended to this document.

Many people suffer from gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. Bloating, cramps, constipation or diarrhea are often symptoms reported during clinical encounters with our customers!

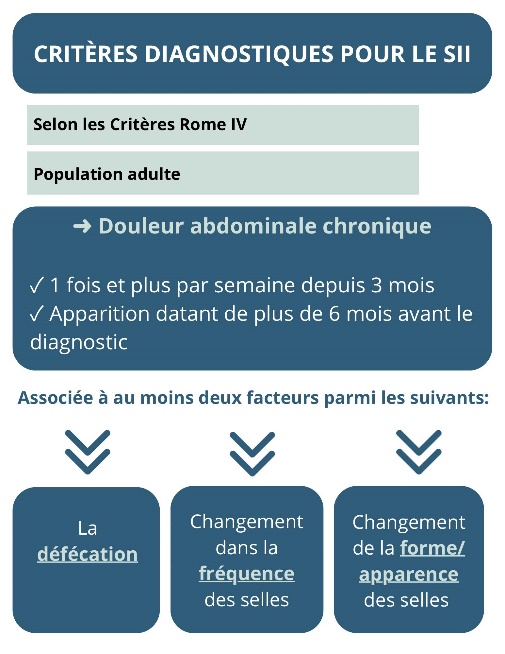

Some people are diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (formerly known as irritable bowel syndrome) based on different diagnostic criteria, depending on the symptoms described and their frequency (2). It is estimated that between 5 and 10% of the world's population has IBS (2). The condition generally affects more women and people under the age of 50 (8, 15).

IBS is categorized into 4 groups (2, 10, 11, 15):

✔ SII constipation (SII-C)

✔ SII diarrhée (SII-D)

✔ SII mixte : alternance entre diarrhée et constipation (SII-M)

✔ SII non spécifié (SII-U)

Adapted from Jayasinghe et al (2023) (11)

As you can see, IBS is a «disease of exclusion», due to the presence of GI symptoms without any disease (e.g. celiac disease, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis) to explain them.

The aim of the nutritional approach is to ensure management of GI symptoms, identify food intolerances (if any), meet nutritional requirements and optimize the microbial health.

Given that GI symptoms are often linked to food consumption, nutrition is at the heart of interventions (1, 3)! In this regard, several organizations, including the American Gastroenterology Association (American Gastroenterological Association) recommend a reference in nutrition for anyone with IBS (1). In addition, the literature reports that subjects with IBS generally have lower levels of vitamin B1 and B2, calcium, iron and zinc compared to subjects without IBS (3).

So you're not alone! But what are the solutions? Is it absolutely necessary to follow the principles of a low-FODMAP diet to improve symptoms?

Let's start with the basics«

Since GI symptoms are highly individual, a personalized approach is essential.

Nevertheless, here are some general nutritional tips to help manage symptoms, based on the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (1, 4, 15, 17).

| Recommendations | Explanations | Applications |

| Reduce’aerophagia ; | Limits intake of ingested «air» to reduce bloating and swelling; | Eat slowly (min. 15 minutes per meal); Chew your food well Reduce consumption of fizzy liquids (e.g. sparkling water, beer); Don't talk while eating; Do not use straw; Do not chew gum; |

| Have a eating routine; | Allows you to spread your intake throughout the day and helps you to listen to your hunger and satiety; | Eat 3 meals a day on a «fixed» schedule; Add snacks as needed; Don't skip meals; Sitting down to eat; Listen carefully to satiety during meals; |

| Reduce gas-generating foods; | Limits «fermentation» in the intestine, which can lead to gas; | Limit the following foods: Cabbage family (broccoli, cauliflower, green cabbage, turnip, Brussels sprouts); Garlic and onion; Pulses (chickpeas, beans); Plenty of raw vegetables; |

| Limit inputs of starches/sugars (carbohydrates) meals; | Consumed in excess in the same meal, carbohydrates promote bloating and distension; | Limit starch intake to ¼ of the plate (bread, rice, pasta, couscous, potatoes, crackers); Limit added sugars (cakes, cookies, soft drinks); Focus on starchy foods that are generally well tolerated (e.g. oats, quinoa, buckwheat, sweet potatoes); Aim for a maximum of 3 fruits a day, spread throughout the day; |

| Limit consumption of foods with sweeteners; | Can cause GI disorders; | Limit consumption of foods containing sugar alcohols (e.g. sorbitol, mannitol, xylitol) and aspartame, such as sugar-free products, candies, gum and diet drinks; ; |

| Limit the amount of fat added; | Consumed in large quantities, fats slow down gastric emptying; | Reduce consumption of fried foods, breadcrumbs, sauces and fatty meats; Focus on fats that are generally well tolerated, in small quantities (avocado, nuts, seeds, oils); |

| Limiting food generally irritants; | Can impair overall digestion; | Limit caffeine, spicy foods and alcohol; |

| To have WATER SUPPLIES suitable; | Helps intestinal regularity; | Aim for 1.5 to 2L of water a day; Make sure you have clear urine during the day; Limit mealtime intake as much as possible, drink between meals; |

In short, the biggest challenge is to find the solutions that work for you! Every case of IBS is unique, which is why we take a personal approach! Make an appointment with one of our nutritionists for an approach that takes your global reality into account!

What about fiber?

Fiber can play two roles in IBS: it can help or hurt! In fact, depending on your symptoms and the type of fiber, it has a different impact (10). Insoluble fibers (e.g. wheat, wheat bran) are generally more fermentable and can cause more bloating, gas and abdominal pain (1, 2, 8, 15). Soluble fibers, on the other hand, are generally better tolerated (1, 2). In this regard, a meta-analysis of 14 randomized controlled studies reported a significant benefit of fiber on overall IBS symptoms (4, 10). In sub-analyses, the benefits were associated with psyllium (more soluble fibers) and not with wheat (insoluble fibers) (4, 10). This is why, in general, the recommended fiber supplements are psyllium and wheat. psyllium or the ground flax seeds (2).

The subject of fiber is highly complex, and needs to be tailored to each pathology and each individual.

Well yes, stress!

We often hear that the microbiota is our 2e brain. To explore these concepts further, see the blog Food and mental health: optimizing cognitive functions through the contents of your plate.

In fact, this relationship is a two-way street, especially when it comes to stress (a state of worry or mental tension caused by a difficult situation). Stress would have an impact on GI symptoms, and conversely, GI symptoms could create stress (4). It is estimated that 70 to 90% of patients with IBS suffer from anxiety and depression (18). Psychological stress impacts on sensitivity, motility, secretion and intestinal permeability (14). Various mechanisms may explain these impacts, including mucosal immune activation, alterations in the central nervous system and the microbiota intestinal tract (14). Stress management through various approaches such as psychological treatments including cognitive-behavioral therapy and pharmacological approaches can be considered (11, 14, 18). Yoga, hypnosis, relaxation, meditation and breathing exercises have also been reported in the literature (1, 7, 11, 15). Laughter may also be beneficial (18). Laughter therapy has been shown to have positive effects on physical and mental health, including changes in the immune system, muscle comfort and hormones (18). Studies have shown that laughter can increase brain endorphins, and that 5 minutes of laughter can release 5 hours of pain (18).

Move, move, move

The benefits of physical activity are well documented, and the gut is no exception! In fact, NICE recommendations encourage the practice of physical activity (2, 15). By respecting GI symptoms, physical activity can speed up GI transit, improve gas release for people with bloating and can help increase microbial diversity (4). In addition, physical activity helps regulate stress and improves mood and well-being (15). A systematic review of 14 randomized controlled studies concluded that physical activity appears to be an effective treatment for patients with IBS (4). Gentle, low-intensity activities are generally recommended, such as walking, yoga, cycling, swimming and aerobics (15).

Of course the microbiota!

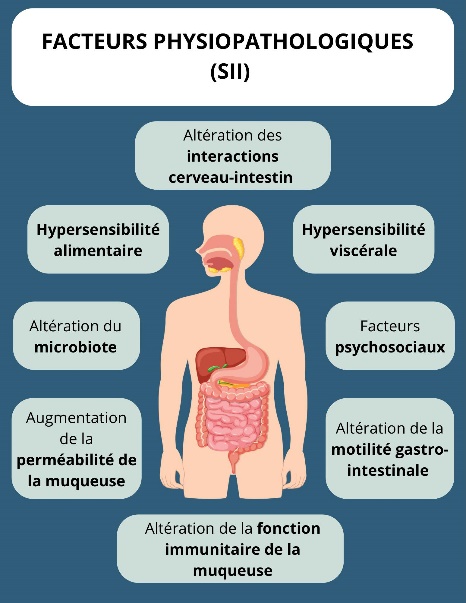

Given that IBS means GI disorders, it's natural to believe that the microbiota has a role to play! Indeed, in various observational studies, the composition of intestinal bacteria differed between subjects with IBS and «control» subjects (2, 6). For example, a reduction in Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria was observed in subjects with IBS (vs. control group) (6, 8). The literature also reports reduced bacterial diversity and increased intestinal permeability in this population (2, 6). In addition, the intestine of IBS sufferers is reported to have a reduced density of endocrine cells (8). Abnormal endocrine expression in the gut leads, in part, to intestinal dysmotility (dysfunction of digestive system muscles or nerves) and visceral hypersensitivity (altered transit and intestinal permeability), mechanisms implicated in some IBS symptoms (8).

Probiotics and IBS

Studying the benefits of probiotics is still a scientific challenge. Each probiotic has a different composition, and our personal microbiota is unique. What's more, different studies use different protocols (duration, dosage) on different populations. In scientific terms, we speak of a heterogeneity between studies, making it difficult to draw clear-cut conclusions on the types of strains and quantities to target (6). Nevertheless, various studies show that taking different strains of bacteria with probiotics can improve overall symptoms of IBS (vs. control groups) (4, 6). In addition to restoring dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota, probiotics may modulate GI motility, positively affect intestinal permeability and reduce activation of the immune mucosa (8). A Clinical Guide exists on this subject, grouping together various studies on products available on the market with different health conditions and their level of scientific evidence.

Click here to consult the guide in question.

For more personalized advice on the possible benefits of a probiotic depending on your symptoms, make an appointment with one of our nutritionists!

So are FODMAPs necessary?

This concept is based on so-called «fermentable» foods in the intestine (13). These carbohydrates are fermented in the colon, causing gas in the lower GI tract (2). To put it simply: your bacteria get «excited» by the presence of certain sugars (FODMAPs), have fun (ferment) and generate gas! By reducing these types of food, the bacteria reduce their associated «reactions» and improve symptoms! FODMAPs can also have an osmotic effect, leading to an increase in water content in the intestinal lumen, promoting its distension leading to symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, flatulence and bloating (2).

In the vast majority of cases, a low-FODMAP diet has been shown to significantly improve intestinal symptoms, with an estimated efficacy rate of 60-75% of cases (12, 16). This approach has been widely studied in the scientific literature and has demonstrated its benefits (1). A meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials evaluated the benefits on intestinal symptoms of the low FODMAP diet compared with other «traditional» nutritional approaches including NICE (5). According to the analyses, the FODMAP approach was superior to other approaches in improving overall GI symptoms (5).

As mentioned, a low-FODMAP diet does not benefit everyone in the same way. Various observations have been made in the literature on «responders» vs. non-responders« to FODMAPs. One of them refers to the function of the colonic barrier and tight junctions...hence the microbiota (16, 17)! More studies are needed to confirm all these observations.

To learn more about the intestinal barrier, permeability and microbiota, check out this blog post Leaky gut: what you need to know!

FODMAP

F Fermentable

O Oligosaccharides

D Disaccharides

M Monosaccharides

And

P Polyols

Examples of FODMAP-rich foodsWatermelon, apple, pear, honey, cauliflower, milk, garlic, onion, wheat, cashew nuts, chickpeas

The low FODMAP diet is a 3-step process (13).

Step 1: Disposal

For 2 to 6 weeks, We've stopped eating foods rich in FODMAPs. In fact, a diet low in FODMAP is not intended for long-term use as there are many foods to limit.

This diet can contribute to vitamin and mineral deficiencies, since dietary intakes of B1, B2 and B9, calcium, iron and magnesium are reduced by its application (3). Hence the importance of being supervised by a nutritionist!

In fact, vitamin D has been studied in several intestinal contexts (3, 15), see the Blog Vitamin D: what's new? for more details.

FODMAPs also have an effect on the microbiota by reducing the diversity of the microbiota and of certain beneficial bacteria, including Bifidobacterium (2, 5, 15). All the more reason not to do it in the long term!

Step 2: Re-exposure

Following the temporary removal of FODMAPs, it's time to «test» which food group(s) are causing GI symptoms, referred to as Step 2 (13). This step is essential to avoid unnecessarily limiting your food choices! In the literature (and clinically too!), it's generally the fructan (e.g. wheat, garlic, onion), mannitol (e.g. cauliflower, celery) and galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS) (e.g. chickpeas, soy beverage) food groups that create symptoms (17).

Stage 3: Reintroduction

In step 3, the aim is to reintroduce foods according to the results for each food group from step 2 to assess tolerance (13).

Lactose intolerance and bovine protein allergies

Lactose belongs to a family of FODMAPs, the disaccharides, being composed of two sugars glucose and galactose (2, 15). For various reasons, including genetic, the enzyme that splits these two sugars, lactase, can be deficient and cause digestive discomfort (2, 15). Thus, when not digested in the small intestine, lactose can cause flatulence, bloating, cramps and diarrhea (2). By testing lactose withdrawal, for example by switching to lactose-free milk and yogurt, you should quickly see an improvement in digestive symptoms if intolerance is present.

This differs from allergy to dairy proteins, including whey and casein (2). These allergic reactions may or may not be immunoglobulin E-mediated (2). Symptoms may include skin lesions, respiratory distress and GI symptoms such as rectal blood loss and severe diarrhea (2).

Gluten vs. wheat

Wheat sugar (fructan) can be a cause of intestinal discomfort. However, some people report discomfort not only with wheat, but also with gluten, which includes wheat, barley, oats, rye and spelt. Indeed, it is possible to have non-celiac gluten sensitivity characterized by the presence of digestive discomfort when consuming gluten, while celiac disease and wheat allergy have been excluded during medical investigations (2, 9). At present, there is no «diagnostic» test for gluten intolerance. Dietary tests of exclusion and reintroduction must be carried out while observing the associated symptoms. What's more, the literature shows no significant benefit from a gluten-free diet in IBS (10, 15). Target your intolerances (wheat vs. gluten) is essential to limit unnecessary restrictions.

As you can see, IBS is a complex pathology, and diet is at the heart of the treatment of associated intestinal symptoms!

Are your symptoms still present after applying these general tips? Would you like to go further into topics such as constipation and diarrhea? Book an appointment with one of our nutritionists to personalize your approach!

References :

(1) American Gastroenterological Association. Chey WD, Hashash JG, Manning L, Chang L. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Role of Diet in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2022 May;162(6):1737-1745.e5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35337654/

(2) Algera J, Colomier E, Simrén M. The Dietary Management of Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Narrative Review of the Existing and Emerging Evidence. Nutrients. 2019 Sep 9;11(9):2162. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31505870/

(3) Bek S, Teo YN, Tan XH, Fan KHR, Siah KTH. Association between irritable bowel syndrome and micronutrients: A systematic review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug;37(8):1485-1497. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35581170/

(4) Black CJ, Ford AC. Best management of irritable bowel syndrome. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2020 May 28;12(4):303-315. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34249316/

(5) Black CJ, Staudacher HM, Ford AC. Efficacy of a low FODMAP diet in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gut. 2022 Jun;71(6):1117-1126. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34376515/

(6) Distrutti E, Monaldi L, Ricci P, Fiorucci S. Gut microbiota role in irritable bowel syndrome: New therapeutic strategies. World J Gastroenterol. 2016 Feb 21;22(7):2219-41. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26900286/

(7) Formation Dietitian Deep Dive, Part 2: IBS D Management including assessment processes, diet interventions, and non diet interventions, 2023

(8) Galica AN, Galica R, Dumitrașcu DL. Diet, fibers, and probiotics for irritable bowel syndrome. J Med Life. 2022 Feb;15(2):174-179. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8999090/

(9) Guandalini S, Polanco I. Nonceliac gluten sensitivity or wheat intolerance syndrome? J Pediatr. 2015 Apr;166(4):805-11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25662287/

(10) Jadhav A, Bajaj A, Xiao Y, Markandey M, Ahuja V, Kashyap PC. Role of Diet-Microbiome Interaction in Gastrointestinal Disorders and Strategies to Modulate Them with Microbiome-Targeted Therapies. Annu Rev Nutr. 2023 Aug 21;43:355-383. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10577587/

(11) Jayasinghe M, Damianos JA, Prathiraja O, Oorloff MD, Nagalmulla K GM, Nadella A, Caldera D, Mohtashim A. Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Treating the Gut and Brain/Mind at the Same Time. Cureus. 2023 Aug 13;15(8):e43404. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37706135/

(12) Monash University, Are you suffering from IBS? Page consulted online: https://www.monashfodmap.com/ibs-central/i-have-ibs/

(13) Monash University, Starting the FODMAP diet. Page consulted online : https://www.monashfodmap.com/ibs-central/i-have-ibs/starting-the-low-fodmap-diet/

(14) Qin HY, Cheng CW, Tang XD, Bian ZX. Impact of psychological stress on irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Oct 21;20(39):14126-31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4202343/

(15) Radziszewska M, Smarkusz-Zarzecka J, Ostrowska L. Nutrition, Physical Activity and Supplementation in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Nutrients. 2023 Aug 21;15(16):3662. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37630852/

(16) Singh P, Grabauskas G, Zhou SY, Gao J, Zhang Y, Owyang C. High FODMAP diet causes barrier loss via lipopolysaccharide-mediated mast cell activation. JCI Insight. 2021 Nov 22;6(22):e146529. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34618688/

(17) Singh P, Tuck C, Gibson PR, Chey WD. The Role of Food in the Treatment of Bowel Disorders: Focus on Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Functional Constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022 Jun 1;117(6):947-957. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9169760/

(18) Tavakoli T, Davoodi N, Jafar Tabatabaee TS, Rostami Z, Mollaei H, Salmani F, Ayati S, Tabrizi S. Comparison of Laughter Yoga and Anti-Anxiety Medication on Anxiety and Gastrointestinal Symptoms of Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Middle East J Dig Dis. 2019 Oct;11(4):211-217. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6895849/